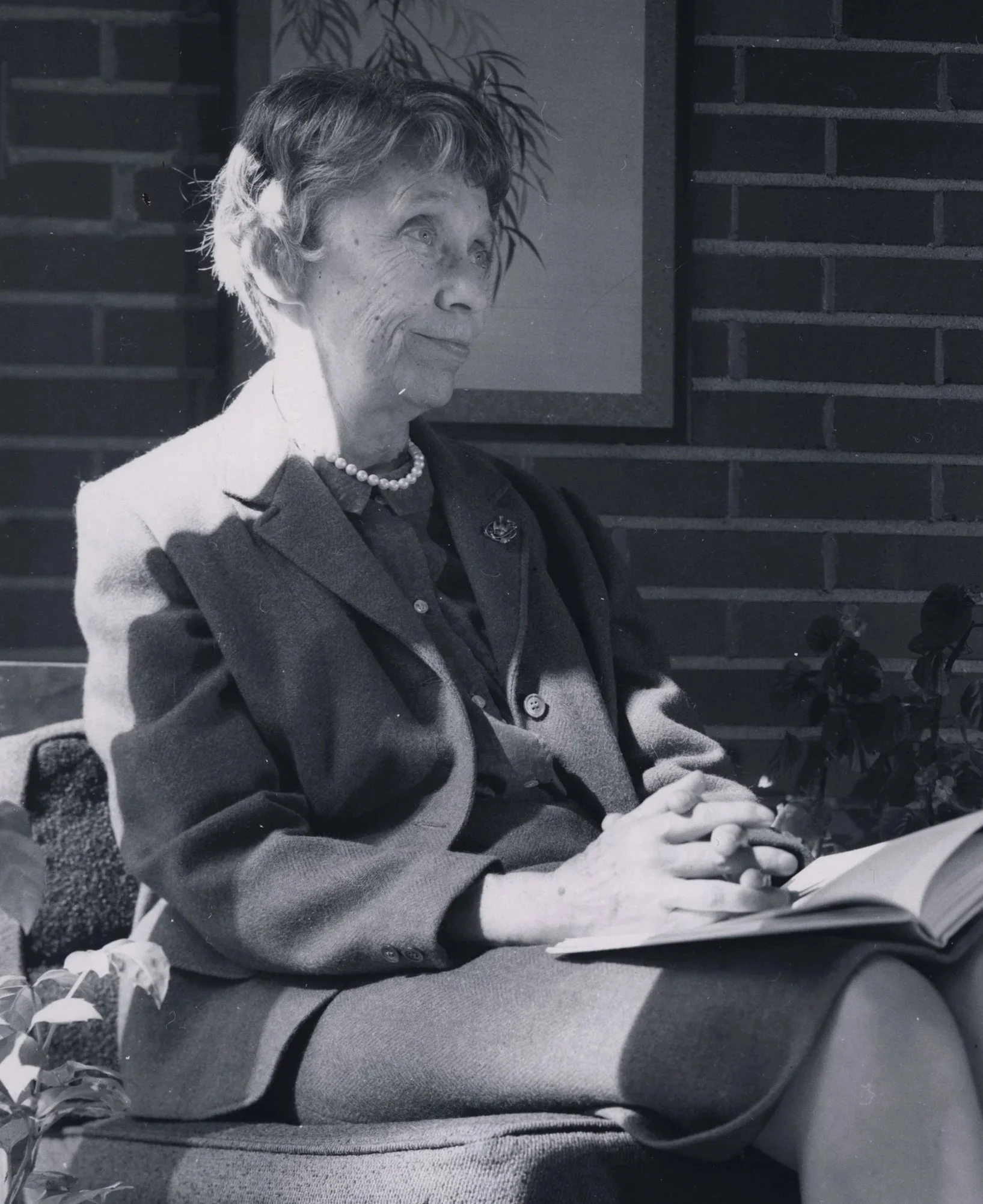

Marjorie Leighey

Raised in Washington D.C., Marjorie Folsom Leighey was a skilled writer, gardener, and committed Episcopalian. She met her husband, Robert Leighey, while attending George Washington University, and the two were married before her graduation in 1931.When the Leigheys were searching for a home in 1947, an advertisement in the Washington Evening Star caught their eye: “FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT house of cypress, plate glass and brick… $17,000.” On their first visit, the couple fell in love with the home’s “organic” design.

This cat-shaped perfume bottle was a gift from Robert Leighey to Marjorie. She kept it in a concealed drawer in her bedroom when public visitors came to tour her home. Woodlawn & Pope-Leighey House Collections, NT2023.1.1a-b.

In the early 1960s, the Leigheys learned that Interstate 66 would be built through their neighborhood. The development was stressful for the couple: “The surveyors were forever measuring on either side of us. The waiting and wondering have taken a few years off our lives.” While the surveyors were measuring around their house, Robert Leighey was admitted to the hospital and passed away from a medical complication on July 29th, 1963. The week of her husband’s death, Marjorie learned that her home was directly in the path of the highway and would be seized through eminent domain. She hired a lawyer, hoping to delay the construction of the highway.

Shortly after Robert’s death, Marjorie agreed to host a visit from preservationists Terry and Hamilton Morton. When Terry, a longtime employee of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, learned the home was in danger, she reached out and requested help from the Trust.

Reassured by growing support from preservationists and Wright fans from across the country, Marjorie was soon giving news and radio interviews to spread awareness of the home’s planned demolition. In March 1964, she sent a letter to the Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, asking for help to save her home. Udall responded immediately, and together they invited preservationists, highway developers, and reporters to meet in her living room and make a plan to save the house.

Pope-Leighey House’s living room after its move to Woodlawn in the 1960s. From the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

There, they decided that the Pope-Leighey House would have to be moved. The National Park Service and the National Trust offered her several locations to rebuild her home. Marjorie chose Woodlawn, the National Trust’s first public site, where she felt the landscape suited the home and that it would be cared for by Trust staff. Marjorie lived in Pope-Leighey House at Woodlawn until her death in 1983, opening her doors to visitors from around the world.

Marjorie’s actions partially inspired the Historic Preservation Act of 1966, helping to preserve countless other historic buildings around the country. Her home was the first Frank Lloyd Wright house to be relocated from its original location.

Explore Primary Sources

Click the images below to read firsthand accounts of life at Pope-Leighey House.